Look, I know we don’t get a lot of traffic to this site. Updating the lab webpage is not very high on my list of priorities. But a completely dead website doesn’t look great – and checking in once in a while proves I have not yet shuffled off this mortal coil.

So what’s new? In brief, a great end to 2023 with:

So what’s new? In brief, a great end to 2023 with:

- Award of an ARC Discovery grant in collaboration with Prof Megan Ryan (UWA), Prof Phil Brewer (Uni Central Queensland) and Prof Caroline Gutjahr (Max Planck Institute for Molecular Plant Physiology). Naturally this was super exciting news! This project will investigate the role of butenolides in plant-fungal symbiosis in barley, one of our top Aussie crops.

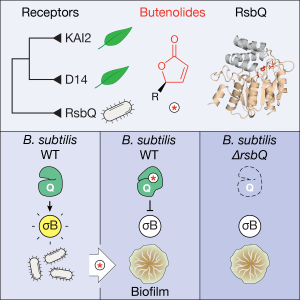

- Publication of our paper in Current Biology: “Perception of butenolides by Bacillus subtilis via the α/β hydrolase RsbQ” led by Kim Melville and Muhammad Kamran, and with valuable contributions from Hugh and Maddy as well. The culmination of a considerable set of experiments that made up the body of Kim’s PhD thesis and learning how to grow and manipulate bacteria, rather than plants for a change. Thanks also to co-authors Max Costa and Nic Taylor for expertise in mass spec technologies. This was a massive achievement, and in the end the publishing experience was a very positive one. In summary: butenolides affect growth and energy stress in the common soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis – because it shares a similar butenolide receptor protein to those found in plants. The big question: do bacteria and plants communicate in some way through a common chemical signalling system?

2024 will be a big year – hoping to see a couple of PhD graduations from the lab and a couple more research papers. Stay tuned… if you’re patient!

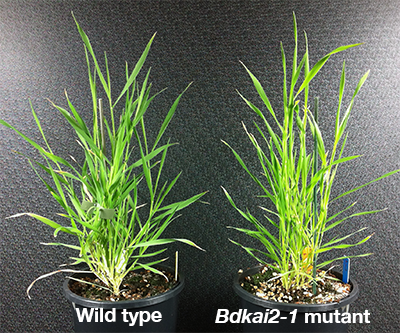

It was back in 2014 when I first thought it would be worthwhile looking into KAI2 signalling in a monocot – and Brachypodium seemed like a decent model that was easier to grow here in Oz than rice! Well finally – actually on Christmas Day 2021 – our findings from characterising two kai2 alleles in Brachypodium were published in

It was back in 2014 when I first thought it would be worthwhile looking into KAI2 signalling in a monocot – and Brachypodium seemed like a decent model that was easier to grow here in Oz than rice! Well finally – actually on Christmas Day 2021 – our findings from characterising two kai2 alleles in Brachypodium were published in

Andy has officially started his PhD, yay! Good luck Andy, and work like stink.

Andy has officially started his PhD, yay! Good luck Andy, and work like stink.